Feb 8, 2021 | Native Hope with Trisha Burke

"The Dawes Act affects me every day," explains Peter Lengkeek, Tribal Chairman of the Crow Creek Sioux Tribe (Hunkpati Oyate). Peter holds out his hand and continues, "Because of the Dawes Act, I own a handful of dirt." His chuckle diminishes to a shake of the head and the release of a sigh. Thinking about the loss of land is difficult for many like Peter, but understanding the effect of the loss — "We have to know where we came from to know where we are going," states the Hunkpati chairman.

Behind the Dawes Act

How does one become a farmer or rancher? Is a plot of land all that is needed? What about money to purchase seeds and tools? What education does a farmer need? Thomas Jefferson made it his mission to make America the land of crops, for if America produced crops the rest of the world desired, the country would be self-sufficient. By the late 1800s, 90% of the population lived on farms.

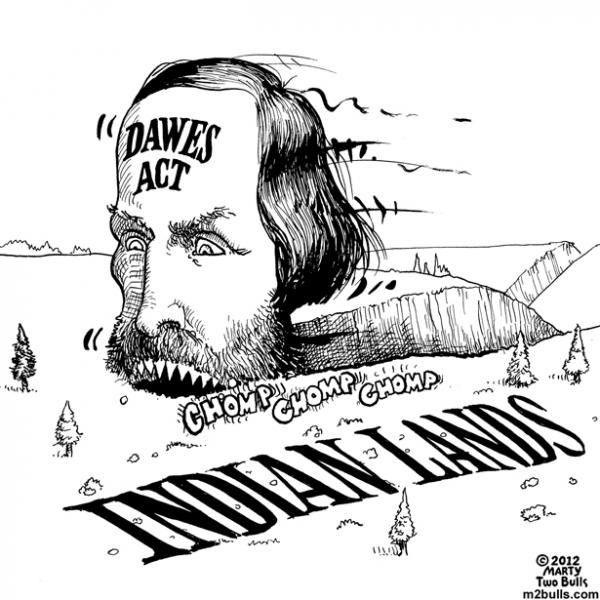

On February 8, 1887—134 years ago, the Dawes Act, also known as the Dawes Severalty Act, became law. At this time in history, Native Americans owned 138 million acres of land across the United States. The Dawes Act's main goal was to create civilized Americans of the Native people through land allotment, thereby solving what the U.S. government and white settlers called the "Indian problem." The U.S. government offered Native American heads of households 160 acres to settle, become farmers or ranchers, and eventually, U.S. citizens. To do this, the Indian would give up his tribal status.

In the eyes of the framers of the Dawes Act, the legislation would bring peace and prosperity for all. For the Native Americans, the law's enactment meant the destruction of tribal culture, the loss of identity, and a massive loss of land—land that was already theirs.

The popularity of the Dawes Act

Most Americans believed the tribal way of life was communistic and uncivil, so the Dawes Act's underlying goal was to break up communal reservation life by making Natives individual landowners. With its passage, the Dawes Act gave the president the power to survey all tribal lands. Surveyors divided the land into tracts from 40-160 acres. Heads of households chose their 160-acre land allotment, or in some cases, the Indian Agent assigned the land. Their children received 80 acres. After all tribal members took their allotments, the reserve land was either sold to non-tribal members or claimed by the U.S. government.

There was not total buy-in by tribes. Chief Sitting Bull, Hunkpapa Lakota, resisted the Dawes Act.

"This land belongs to us, for the Great Spirit gave it to us when he put us here. We were free to come and go and to live in our own way. But white men, who belong to another land, have come upon us and are forcing us to live according to their ideas. That is an injustice; we have never dreamed of making white men live as we live.

White men like to dig in the ground for their food. My people prefer to hunt the buffalo as their fathers did. White men like to stay in one place. My people want to move their tepees here and there to the different hunting grounds. The life of white men is slavery. They are prisoners in towns or farms. The life my people want is a life of freedom. I have seen nothing that a white man has, houses or railways or clothing or food, that is as good as the right to move in the open country, and live in our own fashion."

Even so, the government continued with allotment plans. The Native Americans who received their allotment of trust land found themselves without money, equipment, tools, and education. They were not farmers. They were foragers. They were nomads. Not only were the Natives without the necessary means to become farmers, but also their plots of land were not prime farmland. Additionally, the land allotted to the Native family was held by the U.S. government in trust for 25 years at which time the head of household would gain U.S. citizenship when he obtained the fee simple patent(s) to the land.

To make matters worse, Indians who were farming or ranching their land faced more barriers: a series of Congressional Acts amended the Dawes Act (1887-1934) to diminish Indian land ownership even further. The Dead Indian Act passed in 1902 allowed Indian landowners to sell inherited land, even if it was still in trust. In 1906, the Burke Act passed and added a new stipulation for land ownership: competency. Indian Agents would determine if an Indian was competent and capable enough to own land. Competency could be declared before the 25-year trust period and without the landowner's knowledge, thus removing the land from trust, making it taxable. When the landowner learned of his tax bill, he likely may not have the money to pay, so the land was sold—often to a white settler. The amendments created loopholes and confusion for the Native landowner.

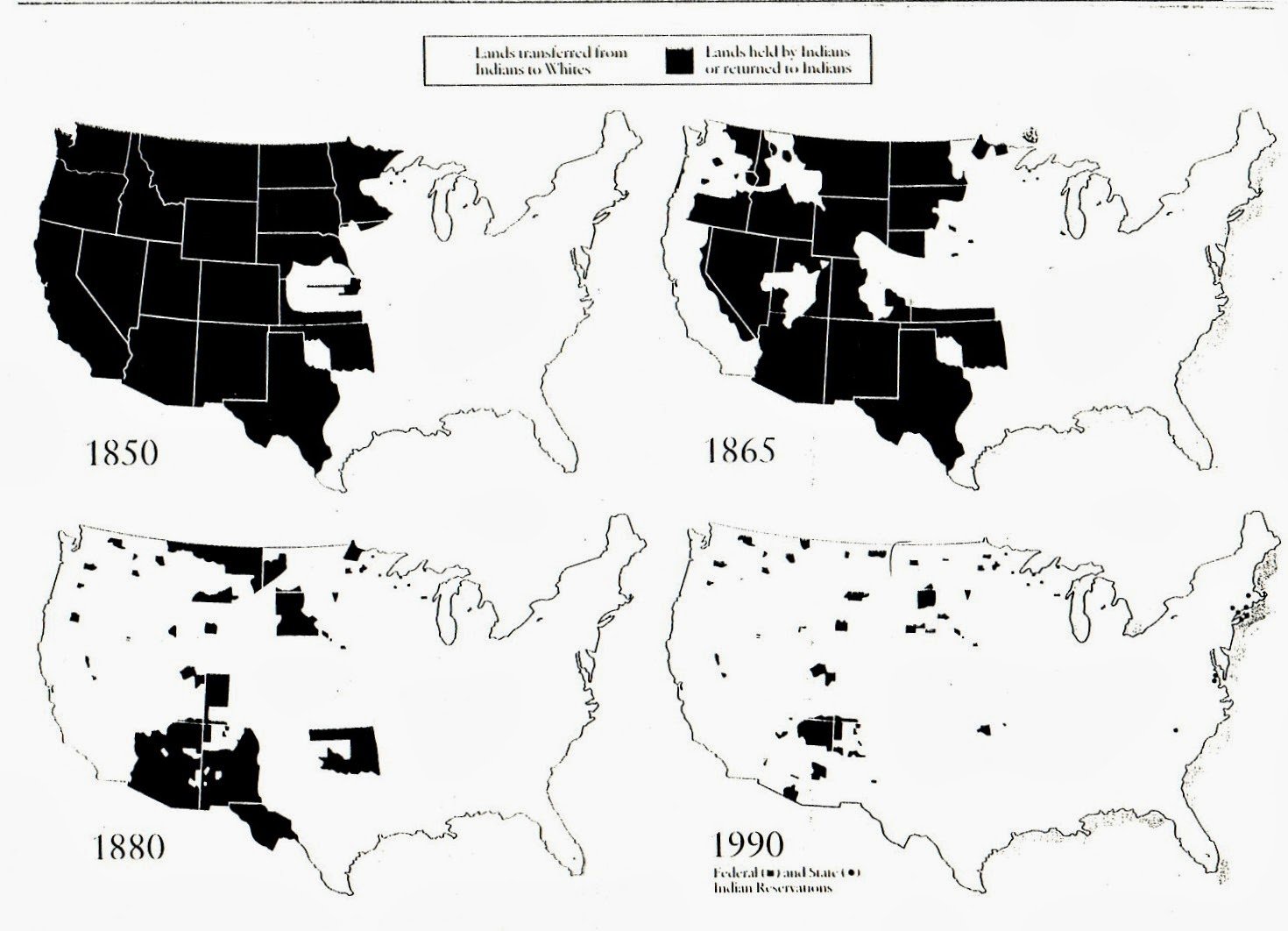

By 1934, Native Americans lost nearly 90 million acres; only 48 million acres remained in their possession. The Wheeler-Howard Act, the Indian Reorganization Act, passed in 1934, ending Indian land allotment, but it did not end the land's fractionization.

Effects of the Dawes Act and its amendments

The Dawes Act inherently called for the fractionization of Indian lands as the ownership of the land is passed down to the heads-of-household children and so on, dividing it up with each further generation.

Peter Lengkeek explains the process via his own experience, "When my mother passed away, her land was divided among her seven children. She had a little over four acres in Fort Thompson, South Dakota — along with some pieces of land on the Fort Peck Reservation in Wolf Point, Montana, on Spirit Lake and Fort Yates Reservations in North Dakota, and on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota."

After his mom died, Peter and his six siblings received an acre of land in Montana. Peter and his brother drove to Montana to see the land. He went to the title office to find out his land's exact location—what he discovered was unbelievable.

"On that one acre of land," he laughs. "There are 938 of us who are owners."

Peter has 938 family members who own a percentage of that one acre of land. The original atí (Dakota for father/head-of-household) was Chief White Bear. As a participant in the Dawes allotment process, Chief White Bear received 160 acres of land. "When he passed away, the land was divided among his ten children, and then, when they passed away, theirs fractionated, and it just keeps doing that until nothing is left," Peter said. "A handful of dirt."

When looking at a map of Indian lands today, there is a noticeable checkerboard effect. This effect is especially true of the Rosebud Sioux Reservation in South Dakota. The reservation has land in several counties in the south-central portion of the state. It includes all of Todd County, but tracts of land lie smattered across Lyman, Gregory, Tripp, and Mellette counties—evidence of the massive loss the Rosebud Sioux (Sicangu Oyaté) experienced. (show map)

.png?width=500&name=Rosebudreservationmap%20(1).png)

Today, Native Americans control 56 million acres of land. Tribes continue to move forward, seeking to repair the Dawes Act's far-reaching effects and other U.S. government policies aimed to assimilate Native Americans forcibly. Last year, in a landmark Supreme Court ruling, Native American tribes won land rights to most of eastern Oklahoma, and in South Dakota, Rapid City’s City Council approved giving land back to the Oglala Sioux Tribe. It is progress like this that reminds how valuable it is for us to know "where we came from" in order for all to heal.

If you haven't already, read the historical events leading up to the approval of the Dawes Act. Read Native American Land and Loss part 1 and part 2.

Please help us raise awareness by sharing this story and the story of Native Hope with your friends and family! When you support Native Hope, you are investing in giving HOPE to the voices unheard.

COMMENTS