Dec 14, 2020 | Native Hope with Trisha Burke

According to Google Maps, the United States of America is 3.797 million square miles (mi²).

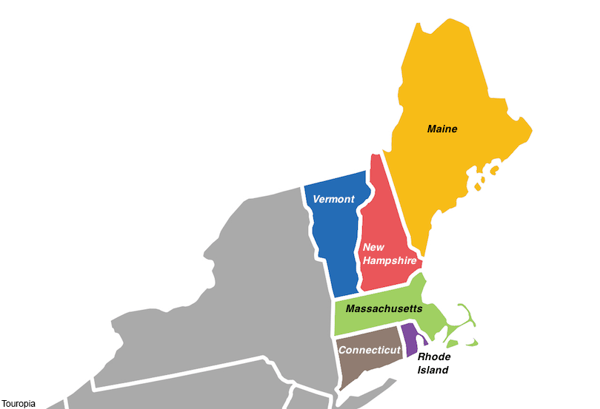

New England measures in around 46,000 mi² (Maine, Vermont, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode Island).

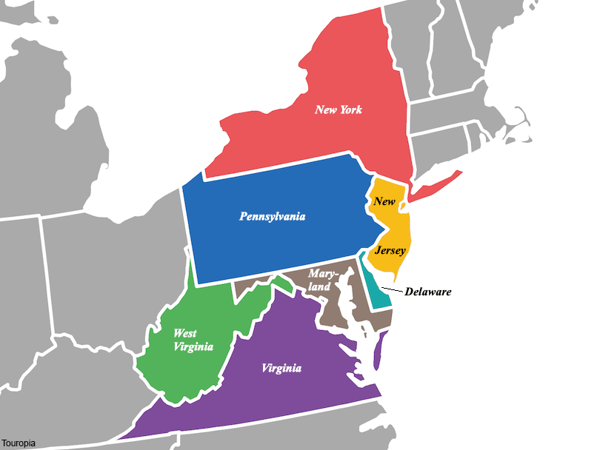

Add 170,000 mi² (mid-Atlantic states of Maryland, New Jersey, Delaware, New York, Washington D.C., Pennsylvania, the Virginias, and half of North Carolina).

The sum equals 216,000 mi²—the amount of land controlled by Native Americans before 1887.

How did Native Americans go from living on nearly 3.8 million square miles to only 216,000 (138 million acres)?

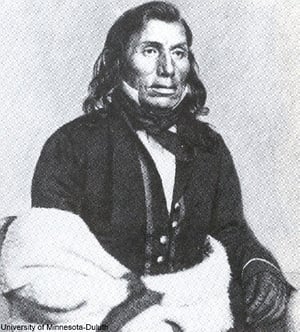

"A little knowledge is a dangerous thing." This phrase, coined in the 1600s, applies to the Friends of the Indian—a group of white, Indian advocates whose efforts paved the way for the U.S. cultural assimilationist policies of the 1800s. Many of these "friends" met Chief Standing Bear of the Northern Ponca, along with Thomas Tribbles of the Omaha Daily Herald, an interpreter, Susette LaFlesche (Bright Eyes-Omaha), and her brother Francis LaFlesche (Omaha). They were on an Indian Civil Rights tour in the East. On this brief four-month tour, Chief Standing Bear spoke - assisted by Bright Eyes - to thousands, who were inspired by many to join the Friends of the Indian and "help the Indian."

By the time Chief Standing Bear and his friends embarked on this tour in 1879, tensions between Native Americans and white settlers seeking land in the West were at their peak. White settlers viewed the Indians as a problem—the "Indian problem" had to be solved. The U.S. government wrote and broke treaty after treaty to gain control of the Indians and pave the way for Westward expansion. It would take an act of Congress to make the most devastating blow to tribal land ownership—the Dawes Act of 1887, but first, the events leading up to the act.

Understanding the history of Westward Expansion

In 1785 the Treaty of Hopewell laid a plan for the U.S. government to begin setting land boundaries or reservations for Native Americans. When signed, this treaty placed the Cherokee under the protection of the U.S. government. The U.S. granted the Cherokee Georgian land, with boundaries. This treaty formed an effort to shape the Indians into Christians and make them farmers. However, the Treaty of Hopewell did not last long—a lust for land brought settlers to Georgia in droves. This created unrest, skirmishes, and the eventual loss of all land to the government (1828). There was no room for the Indian in the South, despite their efforts to conform to Western ways. Most of the tribes were farming, learning English, sending their children to missionary schools, and residing in colonial-style homes—they were assimilating.

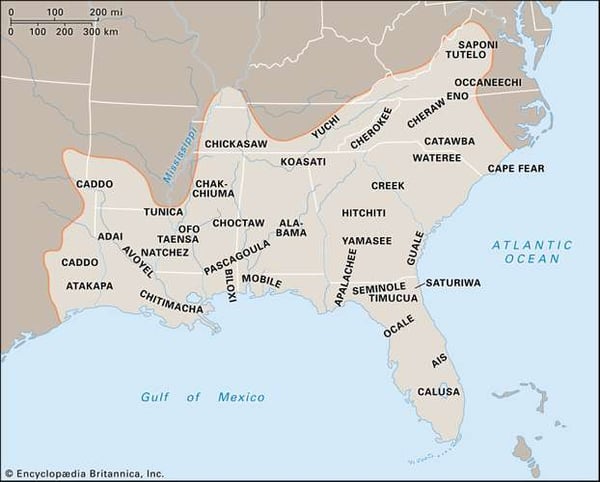

President Thomas Jefferson brokered with France and made the Louisiana Purchase on behalf of the U.S. government in 1803—doubling the size of the United States. Jefferson's plan was to move all Native tribes west of the Mississippi River. The Southeastern Woodland tribes - the Five Civilized tribes (Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Seminole, and Creek) - resisted the idea. Moreover, this unchartered land, the Louisiana Purchase, was already home to hundreds of Native American tribes, many of whom had moved West to escape colonialism. However, the U.S. government and settlers forged into that land as well. The Native Americans proved a formidable and resilient adversary. Conflict after conflict broke out in resistance. Settlers claimed the Indians were barbaric and heathens—something had to be done to quell them.

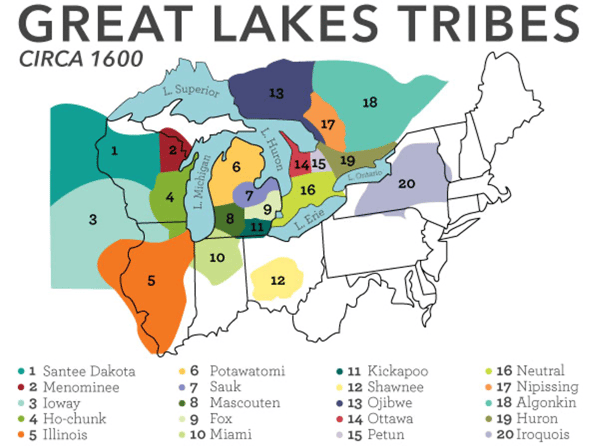

In the Great Lakes region, tribes formed a pan-Indian alliance in 1806 led by Tecumseh, Shawnee. Tecumseh, a great war chief who had fought with the British against the U.S. in the Revolutionary War, refused to sign treaties that ceded land to the government. His multi-tribal alliance (pan-Indian Movement) created a stronghold in the Great Lakes region that vowed to stop the American settlers from moving into the territory. Britain fortified Tecumseh and his followers to protect the U.S. from invading Canada.

In the Great Lakes region, tribes formed a pan-Indian alliance in 1806 led by Tecumseh, Shawnee. Tecumseh, a great war chief who had fought with the British against the U.S. in the Revolutionary War, refused to sign treaties that ceded land to the government. His multi-tribal alliance (pan-Indian Movement) created a stronghold in the Great Lakes region that vowed to stop the American settlers from moving into the territory. Britain fortified Tecumseh and his followers to protect the U.S. from invading Canada.

In 1812, Tecumseh and the pan-Indian Movement joined Britain in a war against the U.S.—Britain promised an independent Indian state in the Great Lakes Region. The Native Americans and the British were successful in defending an American invasion of Canada. The tribes under Tecumseh's leadership taught the British troops Native war tactics, which were unconventional and effective. In 1813, Tecumseh died in battle, and the pan-Indian Movement started to fall apart. Peace talks began, but the tribes continued to wage war, which embarrassed Britain. When Britain and the U.S. signed the Treaty of Ghent in 1814 (ratified in 1815), the Ohio River Valley and much of the Great Lakes region were among Britain's concessions. Thus the pan-Indian Movement lost its claim to the area.

"The Dakota chief Little Crow insisted [of the British]:

'After we have fought for you, endured many hardships, lost some of our people, and awakened the vengeance of our powerful neighbors, you make peace for yourselves, leaving us to obtain such terms as we can. You no longer need our service; you offer us these goods to pay us for having deserted us. But no, we will not take them; we will hold them and yourselves in equal contempt.'

However, many Native Americans were too impoverished by war to join Little Crow in rejecting the presents of consolation."

As a result of America's victory in the War of 1812, Thomas Jefferson's original vision of moving the Indians west of the Mississippi moved forward. General Andrew Jackson led the charge in carrying out Indian removal, primarily from the Southeast. Treaties and talks between Indian nations and the U.S. continued. With each treaty the tribes entered, the more land they ceded to United States. Time and time again, the tribes lost land—relocation was imminent.

In 1830, the Indian Removal Act, sign by President Andrew Jackson, established the relocation of tribes. The act permitted the president to give southeastern tribes and other tribes land west of the Mississippi in exchange for their lands in the East. Also, the U.S. government promised the Indians land ownership and funds for relocation and resettlement. The Five Civilized Tribes of the Southeast resisted—they had established communities, governments, schools, and farms. The promise of a permanent title to land in the unchartered territory was not enticing.

The 1830s marked a devastating loss for these tribes. During this decade, the U.S. military forcibly removed Natives from their homes and marched over 100,000 people to Indian Territory—up to 25 percent died along the way. For example, the Trail of Tears attributed to the deaths of over 5,000 Cherokee. Disease and famine killed them along the 1,200-mile trek.

Likewise, Jackson's policy called for the removal of the Great Lakes tribes in the North. They, too, relocated west across the Mississippi. The same approach forced the southern Great Lakes Tribes from Michigan, Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois from the Midwest to Kansas and Oklahoma. The tribes of Wisconsin proved successful in maintaining a presence in their homelands, but only after numerous attempts to relocate them to Nebraska, Minnesota, and South Dakota.

Photo credit: Milwaukee Public Museum

Photo credit: Milwaukee Public Museum

The aftermath of the removal

The Indian Removal to the Indian Territory (Oklahoma, Iowa, Minnesota, Kansas, Nebraska, South Dakota, North Dakota, Wyoming, Montana) began under Andrew Jackson and extended until 1841 under President Martin Van Buren. As American settlers made their way West, Indian Territory likewise became compromised—the rush for gold in California and other western states sparked this desire.

Compromise after compromise failed. Treaties made. Treaties broken. The Native American lands continued to shrink. In 1851, Congress passed the Indian Appropriations Act, which created the Indian reservation system. The U.S. government made Indians wards of the state and forced them to live within given boundaries. If Natives left the confines, the government punished them or killed them. The government continued its effort to assimilate the Indians effectively. They were to learn to farm, ranch, and convert to Christianity. In 1861, the Friends of the Indians held its first convention in response to the injustices done to Native people.

In Oklahoma, the reservation system seemed to work, but the tribes of the Northern Plains refused to conform. This effort led to wars across the region. America's goal was to make Native Americans meet Western standards of living, which has evoked lasting consequences. The U.S. government, settlers, church leaders, and the Friends of the Indians felt they possessed knowledge to solve the Indian Problem—which proved to be a “dangerous thing.”

Ultimately, the U.S. imposed the Dawes Act in 1887. Read part 2: the Indian Removal Act to the Dawes Act.

Please help us raise awareness by sharing this story and the story of Native Hope with your friends and family! When you support Native Hope, you are investing in giving HOPE to the voices unheard.

COMMENTS