Sep 22, 2020 | Native Hope

“I seem to be standing on a high bank of a great river, with my wife and little girl at my side. I cannot cross the river, and impassable cliffs arise behind me. I hear the noise of great waters; I look and see a flood coming. The waters rise to our feet, and then to our knees. My little girl stretches her hands toward me and says, ‘Save me…’” -Chief Standing Bear, Ponca

History finds a way to show us our future. It leads us to informed decisions and better equips our navigation through trying times. However, it is unfortunate that many facts about the formation of our nation are often absent from mainstream education. A more accurate understanding of our nation’s history and those who shaped it might lead to greater empathy for the journeys of all citizens to the present day.

Altering our view of Native American history

Toy Indians wielding tomahawks, bows with arrows, and war sticks represent a common misconception of Native Americans that has existed for centuries. According to the American West's folklore, all Indians were fierce and warring in nature—Indians loved to fight and attacked white settlers when given a chance. They were wild and untamed. They possessed neither the logic nor the education that made them worthy to stand in a court of law and fight for their rights.

“I am where no member of my race ever stood before. There is no tradition to guide me. The chiefs who preceded me knew nothing of the circumstances that surround me. I only hear my little girl say, ‘Save me.’

In 1879, Standing Bear, a Ponca chief, found himself in a packed federal courtroom in Omaha, Nebraska. He was the first Native American to address a U.S. Circuit Court Judge, Judge Elmer S. Dundy, in a lawsuit against General George Crook, who ordered the detainment of Standing Bear and his tribe at Fort Omaha. Standing Bear and his lawyers, John Webster and Andrew Poppleton, filed a writ of habeas corpus against his tribe’s imprisonment at Fort Omaha. Susette La Flesche, the oldest daughter of the Chief Iron Eyes (Omaha), aptly translated Standing Bear’s thoughts to the judge and gallery of those in attendance.

“In despair, I look toward the cliff behind me, and I seem to see a dim trail that may lead to a way of life.

But no Indian ever passed over that trail. It looks to be impassable. I make the attempt.”

Chief Standing Bear’s life and homeland

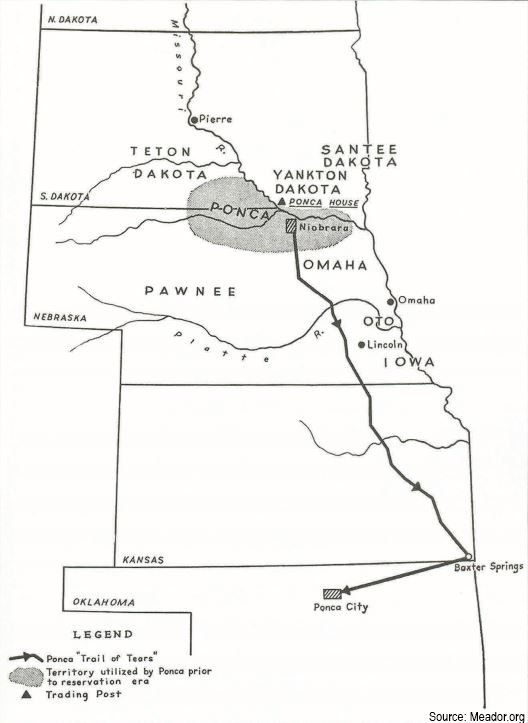

Standing Bear, born around 1829, grew up on the banks of the Niobrara River where it meets the Missouri River, near present-day Ponca, Nebraska. His small tribe, the Usni (Cold) Ponca—originally an Ohio River valley tribe and part of the Omaha tribe, settled there after spending the 1200-1700s living in Pipestone, Minnesota, and Blood Run near Sioux Falls, South Dakota. Because the Ponca seasonally hunted the buffalo, they also lived in The Black Hills and other places in South Dakota, Iowa, and Nebraska.

The Ponca lived in earthen lodges and farmed the land, but when they hunted buffalo, they often encountered their traditional enemy—the Brulé and Oglala Lakota. During the 1700s and early 1800s, the tribes of the Great Plains endured a state of unrest as tribes were forced out of one area and into the next due to the migration of settlers to the West. The Pawnee, Omaha, Ponca, and Lakota vied to control the land and its food supply. By the time Standing Bear was a teen, the Ponca mostly relied on agriculture and area hunting and fishing to provide for its two encampments (northern and southern) of 600 people along the Niobrara.

Tribal control was not the only problem the Ponca faced during the mid-1800s. Westward expansion boomed due to the discovery of gold in California and other states. To quickly organize the Nebraska territory, which was comprised of present-day Nebraska, Kansas, Montana, and the Dakotas, Congress passed the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854. The controversial act created new states and opportunities for settlers to own land.

As a result, the U.S. government pressured Nebraska tribes to sell their land—land that had been once promised to them. Further complicating the situation, tribal lands had overlapping boundaries with multiple tribes claiming ownership. The Omaha Treaty of 1854 dismissed the Ponca’s rights to a strip of land between Aowa Creek and the Niobrara, forcing them to abandon their northern encampment.

In 1858, Standing Bear was a young man and ready to take a position of tribal leadership. In the same year, a treaty required the Ponca to cede much of its land to the U.S. government, leaving the Ponca only a small parcel of land between Ponca Creek and the Niobrara River. The land proved infertile, leading to famine and hardship for the tribe. Other problems persisted as well. The northern tribes continued to raid the Ponca, and the U.S. government failed to deliver on its treaty promises: protection, mills, schools, annuity payments, and supplies.

A new treaty was brokered in 1865. It provided the Ponca the return of their former farm and burial grounds, which lie to the east and north to the Missouri River. Three years later, the U.S. government broke this treaty with the Ponca when it granted Ponca lands to the Lakota in the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868. The Lakota, who had long been laying claim to the land, began raiding the Ponca villages. This conflict persisted until after the U.S. government’s defeat at Little Bighorn [Greasy Grass] in 1876. To keep the Lakota at bay, the U.S. government ordered the Ponca to choose land in Indian Territory (Oklahoma)—the Ponca chiefs refused.

Chief Stand Bear and Ponca's relocation to Indian Territory

Federal Troops forcibly removed Standing Bear and his people (600-800, mostly women and children) in May of 1877. The Ponca walked through harsh conditions without any supplies—they couldn’t take anything. Many died along the 400-mile trek from northeast Nebraska to Oklahoma, including Standing Bear’s daughter Prairie Flower and his wife Shines White.

“I take my child by the hand, and my wife follows after me.

Our hands and feet are torn by the sharp rocks, and our trail is marked by our blood.”

The Ponca arrived in Indian Territory on July 9, 1877—the land was much different from their fertile homelands. It was too late to plant crops. They lived in tipis they had brought with them. Everything was foreign. A third of the tribe died within the first year of relocation. The Ponca chiefs plead for better land, which was eventually granted, and in the summer of 1878, they relocated once again at the Salt River Fork near present-day Ponca City, Oklahoma.

For two summers, the Ponca were unable to plant crops and their food supply was scarce. More died of starvation and malaria—among them: Chief Standing Bear’s eldest son Bear Shield, 16. On his deathbed, Bear Shield asked to be buried where his ancestors lie. Standing promised his dying son he would take him home to the Niobrara. In January of 1879, Standing Bear and 66 followers left Indian Territory and set out on a 600-mile journey to bury Bear Shield in the Ponca homelands of the Niobrara.

Chief Standing Bear's monumental journey

The Ponca faced a now 600-mile journey back to Nebraska in the dead of winter. To further add to the trip's treacherous nature, traveling outside of the reservation was strictly prohibited by the U.S. government, so Standing Bear and his band of a few dozen used rugged trails and often traveled by night. The only wagon used for the journey carried Bear Shield’s body.

After 62 winter days traveling, the Ponca arrived at the Omaha reservation just 100 miles from their home. They were weary, sick, and near death. The Omaha’s Chief Iron Eyes [Joseph LaFlesche] gave them refuge—here, the Ponca ate and rested for the last leg of their journey.

However, before they had a chance to make the last trek, U.S. Army General George Crook arrived with troops to arrest the renegades and escort the Ponca back to Oklahoma.

Chief Standing Bear held at Fort Omaha

Standing Bear and his followers were now prisoners at Fort Omaha, awaiting their long march back to Indian Territory, a march that would mean certain death for most members of the band. However, his promise to his son lingered in front of Standing Bear—it would keep him from giving up without a fight.

Read Part 2 of Chief Standing Bear’s legacy now.

Please help us raise awareness by sharing this story and the story of Native Hope with your friends and family! When you support Native Hope, you are investing in giving HOPE to the voices unheard.

COMMENTS