Dec 19, 2016 | Native Hope

A new fire has been lit at Standing Rock.

The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe (Hunkpapa Oyate) found its voice in mainstream media peacefully protesting the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL). On April 1, 2016, the Sacred Stone Camp was established as a spiritual camp to block the DAPL.

As the protest grew, the Oceti Sakowin (Seven Council Fires) Camp was formed when hundreds of people traveled to Cannon Ball, North Dakota, to join the effort. Here a “historic gathering of tribes, allies, and people from all walks of life standing in solidarity” reminded the world that “Mni Wiconi” or “Water is Life.”

On November 15, as is tradition, a ceremonial fire was set at the Oceti Sakowin Camp. It represented the “heart of the ancestors” and gave hope that the children of the Seven Bands of Lakota would live.

Thousands of protestors or “Water Protectors,” as they prefer to be called, make up three camps, with the Oceti Sakowin Camp serving as the main. On December 4, the water protectors effectively halted the Dakota Access Pipeline with their NoDAPL campaign. (See the New York Times interactive map.)

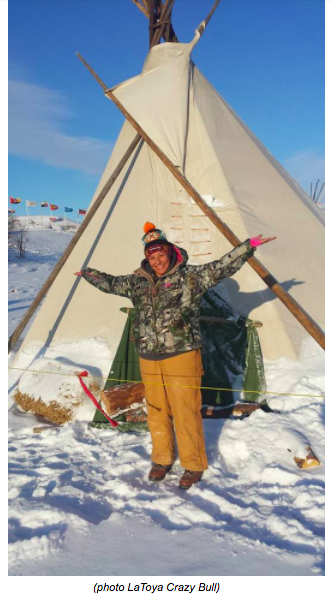

LaToya Crazy Bull, water protector and member of the Lower Brule Tribe (Kul Wicasa Oyate), explains, “The Oceti Sakowin Camp is no more; the main campfire is out. Now it is called Oceti Oyate [the people’s] Camp, and a new fire has been lit [December 11].”

She continues, “The new fire was lit because the first sacred fire for Oceti Sakowin served its purpose. It was told in a dream and in ceremony that we have to believe in our prayers and put that fire out now.”

With the lighting of the new fire, the Oceti Sakowin Camp did not relocate. Instead, it now has a new purpose and vision of looking after the people; thus it has been renamed “Oceti Oyate.” It will carry the people into the next era of the fight for clean water and respect for Mother Earth.

So, LaToya remains with at least a thousand other protectors who intend to stay until the DAPL is stopped completely. She and the others have winterized their camps and maintain belief that their efforts will make all the difference.

Why did they come?

LaToya answered the call from the elders for help to protect the water. She explains, “When an elder asks something of you, traditionally, you do what you are told.” With that, LaToya traveled from Lower Brule, South Dakota, and joined the peaceful protest in August.

In a sense, the international spotlight is shining on LaToya and her family of water protectors. #NoDAPL has earned the attention of celebrities, dignitaries, and religious leaders. Their peaceful cry: “Mni Wiconi” has been seen on posters, flags, t-shirts, banners, and newscasts in protests around the United States and beyond. All protectors are representing their Native American culture and their sacred lands.

Who are the protectors?

The effort to protect the waters of the Missouri River has awakened Indian country and brought forth young leaders who are united in a common cause. Like LaToya, many of them are standing on the front lines, but others like Jordan Daniel, a member of Kul Wicasa Oyate, are leading the charge in other ways.

(photo Jordan Daniel)

(photo Jordan Daniel)

Jordan works as an advocate for Native American rights in Washington, D.C. and uses her voice to create awareness about issues facing Indigenous people. “Everyone is coming together, and there is that strong collective voice,” she ascertains. “The movement that’s happening right now is absolutely beautiful, and I would like to see that sustained past NoDAPL. If we can keep all these non-Native allies that we have right now in this fight with us, I definitely think there will be large impactful changes for the Indigenous communities.”

(photo Jordan Daniel)

(photo Jordan Daniel)

What is the Dakota Access Pipeline?

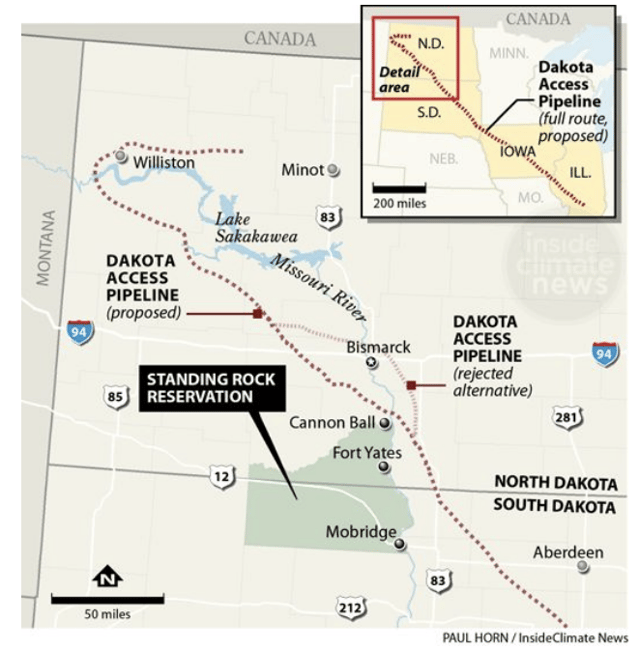

According to one of the main developers, Energy Transfer Systems (ETS), “The Dakota Access Pipeline Project is a 1,172-mile pipeline that will connect the Bakken and Three Forks production areas in North Dakota to Patoka, Illinois. It will transport approximately 470,000 barrels or more per day.” Currently, this crude oil is transported by rail.

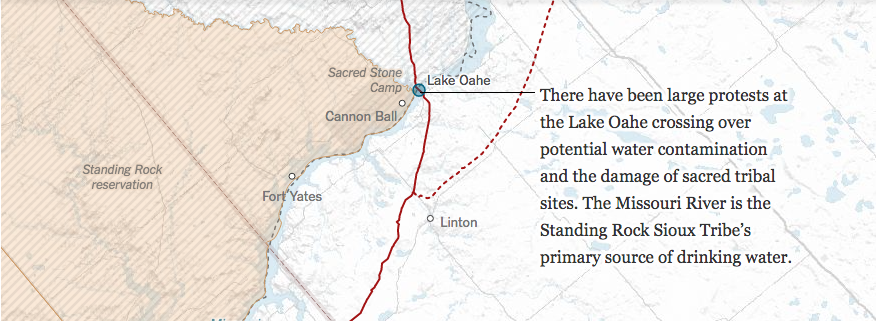

What is the pathway?

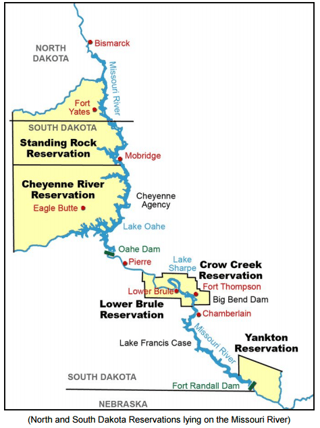

Traversing the states of North Dakota, South Dakota, Iowa, and Illinois, the pipeline would span the Missouri River, a chief water supply for the tribe and thousands of others downstream. The pipeline would also cross over the historic Cannonball Ranch, which houses “known and unknown” burial grounds for the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe (Hunkpapa Oyate, Chief Sitting Bull’s Oyate).

The ranch’s land, at the center of the controversy, has now been sold to Dakota Access, LLC, which further complicates the issue at hand because this could lead to the desecration of sacred burial grounds.

Faith Spotted Eagle, a grandmother and water protector from the Yankton Oyate, explains that the land in question is a “multi-component site,” meaning there are layers and layers of events that have happened on the land.

Faith Spotted Eagle, a grandmother and water protector from the Yankton Oyate, explains that the land in question is a “multi-component site,” meaning there are layers and layers of events that have happened on the land.

“I think the most effective way we could get that point across is if all of the sudden the Oceti Sakowin [water protectors] decided to build a project through Arlington Cemetery,” explains Faith. “I think the point would be taken that you don’t disturb people who have been put to rest.”

How does water fall into play?

“I am here to advise anyone that will listen, that the Dakota Access Pipeline is harmful,” says Dave Archambault II, chairman of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe (Hunkpapa Oyate). He asserts, “It will not be just harmful to my people, but its intent and construction will harm the water in the Missouri River, which is the only clean and safe river tributary left in the United States.”

It is this reasoning that in part prompted the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe to file a federal lawsuit against the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in July. The lawsuit claims that the DAPL violates the National Historic Preservation Act and the Clean Water Act, among other laws.

The pipeline was set to cross Lake Oahe, a large reservoir behind Oahe Dam on the Missouri River, just a half mile above the Standing Rock Reservation. “Oahe” is Lakota for “foundation,” and those protecting the waters believe that the Missouri River is just that—the foundation of life and their culture.

Reuben Fasthorse, the Lakota Magician, is a member of the Hunkpapa Oyate. When asked his thoughts about the protest, he shares, “I would say that the protestors are not only there out of fear, but also out of anger. Fear of our drinking water being contaminated. Anger because the Army Corp of Engineers flooded the Missouri, and we lost burial sites and land.”

Many share Reuben’s sentiment, and this assertion has resonated with Indigenous tribes and supporters from across the world. Over the past several months, the protest has grown into a camp of thousands.

(photo Jordan Daniel)

(photo Jordan Daniel)

What effect has this had on the next generation?

“I think it is a rebirth of a nation. I think that all of these young people here dreamed that one day they would live in a camp like this because they heard the old people telling stories of people living along the river,” Faith Spotted Eagle told CNN. “They heard them talking about the campfires and the horse nation, and they are actually living it—living the dream.”

The camp might seem like an impossibility to many—unsafe in this day and age. But, for the Lakota, the camp represents something they lost just over a century ago: a way of life. Their ancestors lived off of the land and remained a vital people without modern luxuries. It was called the “Lakota Way”—a way of honoring Mother Earth, her inhabitants, her land, and her water.

Many would say that the NoDAPL is not a protest but rather a movement. It is a movement to stop what they see as the destruction of Mother Earth. It is a spiritual battle—one they are fighting with prayer.

One Lakota man explains, “The movement is not out of hate but out of love. Songs of love for Mother Earth and her life blood, the water, can be heard nightly [around the camp].”

More than anything, the camp seems to be creating that sense of identity that Faith mentioned. LaToya posted on Facebook: “Being at Oceti Sakowin has given me a sense of belonging, a sense of hope. My Ina' [mom] raised me to stand up for what I believe in and to always help others. I am able to do that every day. Also I've met so many people that have become my family.”

Jordan adds, “I definitely think this generation right now...they’re going to be a huge catalyst in things changing. They’re having a stronger voice and sticking up for themselves, but also bringing people together as well.” She believes that a strong collective voice will make a difference within our communities and empower future generations.

What’s next?

On December 4, 2016, the Department of the Army’s website declared that they “will not approve an easement that would allow the proposed Dakota Access Pipeline to cross under Lake Oahe in North Dakota.” They declared that this decision was based on a need to explore alternate routes for the Dakota Access Pipeline.

The Army’s Assistant Secretary for Civil Works, Jo-Ellen Darcy, stated, "Although we have had continuing discussion and exchanges of new information with the Standing Rock Sioux and Dakota Access, it's clear that there's more work to do. The best way to complete that work responsibly and expeditiously is to explore alternate routes for the pipeline crossing."

Meanwhile, LaToya and Jordan know this is a small victory in a much larger war. It seems that until the alternate route is announced, the international spotlight will remain on the water protectors of Standing Rock who stand united in their efforts.

(photo Jordan Daniel)

(photo Jordan Daniel)

Native Hope commends LaToya, Jordan, and other young leaders who promote the Lakota Way and strive to ensure a place for the next generation. They are truly following in the footsteps of Chief Sitting Bull who said, “Let us put our minds together and see what life we can make for our children.”

COMMENTS