Nov 21, 2019 | Native Hope

*The name of this individual has been changed to protect identity.

Michael* a transfer student from a neighboring tribal school, made his way to his desk—hoodie masking his drained eyes, body dragging beneath. Normally, I might have asked him to remove his hood, sit up, and engage; however, his despondent look informed me otherwise. Not only has it been my understanding that each and every one of us carry baggage but also my hope to help alleviate the weight for those who seem incapable of taking another step. That day, Michael seemed to possess that particular weight.

His narrative, along with numerous others’, inspired me to leave the classroom after 24 years and delve deeper into the issues facing Native people in my community. That narrative, or lack of narrative, is what has long been plaguing our nation’s first people for centuries. They were stripped of their land, their customs, their languages—their way of life.

“A people without knowledge of their past history, origin, and culture is like a tree without roots” -Unknown.

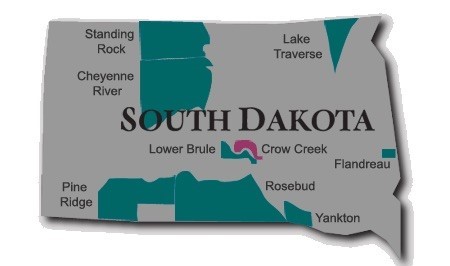

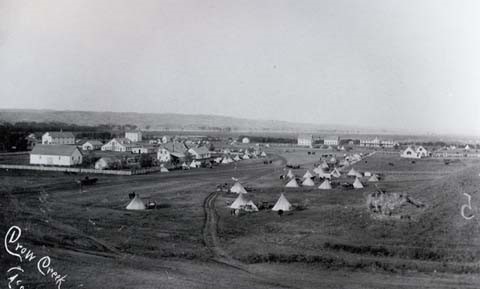

It is difficult to illustrate the crises facing residents of the Crow Creek Indian Reservation without emotional and historical context. Without making this a story that borders on “poverty porn” nor inspires the proverbial “white guilt,” my aim is to illustrate, without mincing words, important facts in order to expose a narrative of historical loss that is all too common among Native communities.

What is Michael’s Story?

“Just like a building—I’m not going to worry about anything beyond my basic needs—that foundation is NOT stable, so why worry about anything above my immediate needs: food, shelter, warmth” -Crow Creek tribal member.

When Michael entered my classroom that morning, he was more than tired. He was worn down, he was hungry, he was lost. He readily ate the granola bars I quietly placed in front of him; then he slept, in an upright position, under the veil of the hoodie. After class we talked.

He explained that when he arrived home from his basketball practice, his mother was drunk, not the ordinary drunk, worse than normal. Needless to say, there was no dinner for him or his siblings—just an ongoing fight for the evening. She wanted the car keys, but he refused to give them to her. At two in the morning, Michael heard a loud crash outside—his mother had thrown a brick through the window of their car and was in the car searching for the second set of keys. Chaos ensued.

I tell this story as a means to discuss some of the root issues. Alcohol has gravely affected many on the reservation. Used for self-medication of much deeper issues, the bottle is an escape. Unfortunately, like many, Michael’s mother found herself addicted to this “medicine.” It masked the pain of no job opportunities, lack of resources to provide for her children, her personal trauma, and a hopelessness that had become overwhelming.

Michael’s hoodie protected him day in and day out from a lack of foundational needs: stability at home, regular meals, and a safe place to sleep.

FACTS: Alcoholism remains a severe health risk for people on the reservations, but the perceived stereotype that all Natives are alcoholics has likewise created damage for Natives socially, economically, and emotionally. In fact, “...stereotypes held by EuroAmericans of the Indigenous peoples were persistently condescending and dismissive at best” which has created numerous barriers in the mainstream job market. Unfortunately, this stereotype has existed since the colonists presented alcohol to the Indians of the Americas.

Moreover, Indian Health Service [IHS] is underfunded, so there is a lack of resources available to address the mental and physical health needs due to alcoholism/drug abuse. This does not imply IHS is to blame for lack of treatment—the underfunding of Indian health care is a systemic issue of the U.S. government’s treatment of Native Americans. “Life or limb” has been the long-standing adage in regard to healthcare for Natives, which means that unless something threatens a person’s life, treatment is discretionary, thus treatment for alcoholism and it’s underlying causes falls through the cracks.

When discussing the treatment of alcohol abuse, it is important to note: “Researchers found that Native Americans are more likely than white counterparts to abstain from alcohol altogether, and the two groups had comparable rates of heavy and binge drinking.” -Washington Post

- “We tested the belief that Native Americans [NA] have elevated alcohol consumption.

- Using national samples, we compared NA to whites on a range of drinking measures.

- NA use rates were similar to or less than those of whites across all of the measures.

- These findings can be used to help correct misinformation on NA alcohol consumption.”

Thus, it is far more likely that the socioeconomic conditions and historical trauma play a direct correlation to the use and abuse of alcohol for Native people. To further understand the complexities of the historical loss, research by Dr. Maria Yellow Horse Brave Heart provides ample connection between loss, trauma, and substance abuse as a tactic to numb this pain.

Housing Crisis on Indian Reservations

Like many on his reservation, Michael lived in an overcrowded, multi-generational home. His house stands in a remote, rural housing district on a gravel road with a dozen or so other homes. There are many factors leading to the “remoteness” of Michael’s community: few in the community have cars, and if they do, the reliability of the vehicle is limited as is its fuel; there is one road—in and out; the distance from “town” is 10 miles; the nearest school is 30 miles— either north or south; this “community,” like many on reservations, is mainly made up of relatives of one tiospayé (extended family).

However, because most people cannot afford to build their own homes, many tribes have a massive housing shortage problem, with a housing wait list system. The list is long, as many as 70-80 people are on the list for housing at a time, and people often wait for 7-8 years for a house. For this reason, most Native people live with their extended families in small homes while they wait for their own house.

These homes, like Michael’s, have 2-3 bedrooms which may seem adequate for the average family. But according to Joseph Shields, director of the Crow Creek Housing Authority [CCHA], there are around 2500 residents on his reservation and roughly 220 homes available. That means on average each home houses 12+ people with families doubling and tripling up in order to have shelter.

Each family without a home to call their own is considered homeless. On the Crow Creek reservation, there are upwards of 300-400 homeless people, if all were to report their living situations to the housing authority. Why does this create a problem? “Overcrowding, substandard dwellings, and lack of utilities all increase the potential for health risk, especially in rural and remote areas where there is a lack of accessible healthcare.”-American Aid

“Living in a multigenerational home can be a blessing to some, but to others and even at the same time, it can be suffocating to say the least. It often causes familial problems because different generations can bring different rules and expectations of cleanliness, etc.” -a Crow Creek Community member. As a result of the lack of housing, many people lack the privacy and space a family needs in order to thrive.

FACTS: Reservations began as prisoner of war camps. Life on these reservations was dismal and destructive for the people and their way of life. Foundational needs were not met. “...Indians on the reservations suffered from poverty, malnutrition, and very low standards of living and rates of economic development”-Kahn Academy.

“The main goals of Indian reservations were to bring Native Americans under U.S. government control, minimize conflict between Indians and settlers and encourage Native Americans to take on the ways of the white man. But many Native Americans were forced onto reservations with catastrophic results and devastating, long-lasting effects.” History.com

Families were given plots of land and U.S. citizenship; however, in most cases, plots of land were miles apart from one another and housing was limited. Thus, the government systematically separated the tribes into “manageable” groups further isolating them.

Despite the efforts to “manage,” even destroy, Native American culture, Natives have proven resilient. Today, they make up 1-2 percent of the American population. They have relied on one another for survival for hundreds of years; however, a new threat has arrived.

Meth has taken control of these communities. “The rate of meth use among American Indians is the highest of any ethnicity in the country and more than twice as high as any other group,” according to the National Congress of American Indians. It is highly addictive and when smoked it permeates the sheet rock, wood, and other porous materials of a house The housing crisis is a reality that has become a silent killer.

Meth’s Effect on the Housing Crisis

On Michael’s reservation many homes have been contaminated to the point that they are unlivable. What this means for this community of 2,500 people is homes would have potentially housed over 100 residents, but now the homes stand vacant and contaminated.

Why can't the Crow Creek Housing Authority fix the homes and move new families in as soon as possible? Like IHS, CCHA’s funding is reliant on federal government dollars. These funds are tied up in a long, involved grant process—delivery of funds lags behind 6-9 months, according to CCHA director. This delay prevents CCHA from ordering the necessary materials in a timely manner, leaving people waiting for much-needed housing.

COMMENTS