Feb 20, 2017 | Native Hope

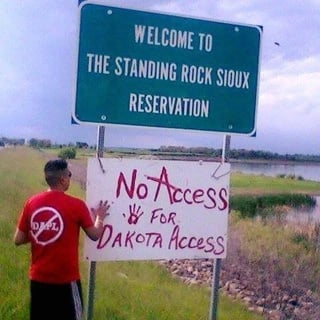

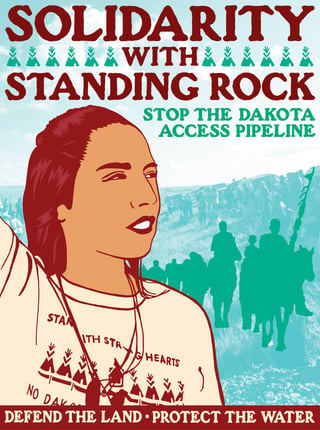

#NoDAPL (Dakota Access Pipeline) and “Stand with Standing Rock” have become rallying cries for the next generation of American Indians. Yes, it is about the water, “Mni Wiconi” (Water is Life), but beyond that #NoDAPL represents a notion that it is time for the voice of the Indigenous people to be heard.

The cry has been picked up by thousands around the world; in fact, with Pope Francis weighing in and Paris Jackson giving a shout out during the Grammy Awards, it has become evident that #NoDAPL is still very much alive—in spite of President Trump’s executive order for Energy Transfer Partners to resume construction on the last section of the 1,172 mile pipeline that will carry fracked, crude oil from North Dakota across five states to Illinois.

With this latest executive order, learning about the young people behind the cry #NoDAPL seems imperative.

What does it take to start a movement?

One voice. Then another. And another. Soon there is an avalanche of voices that are heard ‘round the world. Oh, and having Facebook, Twitter, and Snapchat helps, too! This is how Bobbi Jean Three Legs, Standing Rock Sioux Tribe (Hunkpapa Oyate), first thought about the idea of protesting the pipeline.

Bobbi Jean saw a picture on Facebook toward the end of March 2016. She remembers, “I came across this picture of Jonathan Edwards and several other individuals standing in the middle of a street in McLaughlin, South Dakota,...standing there holding up their signs [protesting the pipeline].”

Bobbi Jean saw a picture on Facebook toward the end of March 2016. She remembers, “I came across this picture of Jonathan Edwards and several other individuals standing in the middle of a street in McLaughlin, South Dakota,...standing there holding up their signs [protesting the pipeline].”

Around this same time, Bobbi Jean’s relative called her and told her more about the pipeline. She explained to Bobbi Jean what DAPL would mean for Standing Rock and what it could do for the future of the tribe. Immediately, Bobbi Jean thought about her daughter, Chloe, and the youth basketball players with whom she worked.

“I don’t know why she was calling me! I didn’t know anything about pipelines, and I’d never fought against them or anything!” Bobbi Jean laughs. “But, she just kept saying, ‘We need to do something; we need to do something.'”

With her relative’s guidance, Bobbi Jean decided to organize a run. She made flyers, and she went door to door in Wakpala, South Dakota,  asking for support from her community members—asking them to run, walk, or even drive behind the youth to create awareness about the DAPL. On the first run, there were about 30 youth who gathered “only a few hills from where Chief Gall [former leader of the Hunkpapa Oyate] had his encampment.”

asking for support from her community members—asking them to run, walk, or even drive behind the youth to create awareness about the DAPL. On the first run, there were about 30 youth who gathered “only a few hills from where Chief Gall [former leader of the Hunkpapa Oyate] had his encampment.”

An elder gave a blessing and a talk in Lakota that Bobbi Jean’s father translated for the youth. He said the elder asked, “Do you understand what you are about to start?” Next, the elder explained that the water was sacred and its own being, and he said, “If you do this, it will follow you wherever you go.” Then, he prayed for them before and after the first 11.1 mile run which was along the Missouri River from Wakpala to Mobridge, South Dakota.

The power of unity

A week later, a group of the Keystone XL Pipeline fighters from the Cheyenne River Reservation came to Wakpala where they met some members of Hunkpapa Oyate. They suggested that a camp should be established for those interested in stopping the  DAPL. It was then that LaDonna Brave Bull Allard, Hunkpapa elder and historian, offered her land where the Cannonball River joins the Missouri River, for what would soon become the Sacred Stone Camp.

DAPL. It was then that LaDonna Brave Bull Allard, Hunkpapa elder and historian, offered her land where the Cannonball River joins the Missouri River, for what would soon become the Sacred Stone Camp.

Bobbi Jean explained that on April 1, 2016, there was a horse ride and caravan from the Standing Rock Tribal Chairman’s office to LaDonna’s land near the Cannonball River to open the camp. “That was the first time in my life where I was a part of something like that," she recalls. "It was really powerful watching them ride in like that!”

Originally, the Sacred Stone Camp was to be a small prayer camp with only three or four people staying. In order to support the effort, Bobbi Jean and Chris Walton, her boyfriend, joined the camp in its third or fourth week. It was then that LaDonna asked her to help lead and organize a 500-mile run from Cannon Ball, North Dakota, to Omaha, Nebraska.

Bobbi Jean teamed up with other coordinators like Joseph White Eyes and Jasilyn Charger of Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe to plan the run. Twelve runners completed the run in about eight days. “Literally, everyone I asked to go either thought I was crazy, or they were too busy,” she laughs. Out of the twelve runners, five or six of them were youth from Standing Rock who just jumped in, dropping everything.

Her dream was to have a runner for each of the nine reservations of the Oceti Sakowin bands. This is how Daniel Grassrope of the Lower Brule Sioux Tribe (Kul Wicasa Oyate) became involved. He messaged Bobbi Jean and said he would represent his people. He told Bobbi Jean, “This is what I have prayed for all of my life.”

The coordinators designed a route which would go through as many reservations as possible. The runners stopped in communities that opened community centers or churches for them to sleep in. They ran in a traditional messenger style where the runners replaced one another when necessary. “I saw so many young people blossom and find their voice,” Bobbi remarks. “It was life-changing.”

She met so many unique people along the way. In Winnebago, Nebraska, a Lala (grandpa) with a cane wanted to run with the group but couldn’t. Bobbi Jean took the privilege of walking four miles with him. According to her, it was the best conversation she had ever had in her life.

He said, “You know, there are going to be a lot of people who aren’t going to agree with you, but that’s okay. When people look at you guys and know that you are running, that will make them uncomfortable. And when you guys make yourselves uncomfortable, then you are making us [people] think about it." This really put the group’s effort to raise awareness into perspective for this young mother and warrior.

The group made it to the steps of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers' office in Omaha on May 3 where a representative accepted their petition to deny the easement to drill under Lake Oahe (a dammed section of the Missouri River, the fourth largest reservoir in the United States). Feeling empowered and motivated, the group returned to Standing Rock and the Sacred Stone Camp.

This is just the beginning of the story...read part 2 here! At Native Hope, we believe in honoring American Indians and their culture with a message of hope and dignity.

COMMENTS