Sep 24, 2024 | Native Hope

The earliest schools for Native Americans were most often mission schools, founded by different religious groups in the United States, Mexico and Canada. In 1819, Congress passed the Indian Civilization Act, in which they paid missionaries to educate Natives and promote the "civilization process."

In some cases, depending on the religious order and the period of history, Native American children were forcefully relocated and brought to these schools, where the United States began assimilating them into the Western way of life. In other cases, groups set out to “help” Native Americans in well-intentioned albeit misguided efforts to respond to their situation

Thus began the long and harrowing journey of Native American boarding school history that has caused trauma for Native Americans that is still felt by current generations.

Native American Education History

Native American Education History

In the late 19th century, mission schools gave way to federally-funded schools in which the government took a more direct role. In many cases, these schools were run by religious orders, though not all schools run by religious orders received federal funding. Various Native American boarding schools were established across the country, the most famous of which was the Carlisle Indian School, built in 1879 in Carlisle, Penn.

Founded by Colonel Richard Henry Pratt, this is where the term "Kill the Indian to save the man" was coined, which represented the belief system behind these schools. The intent was the erasure of Native culture through assimilation.

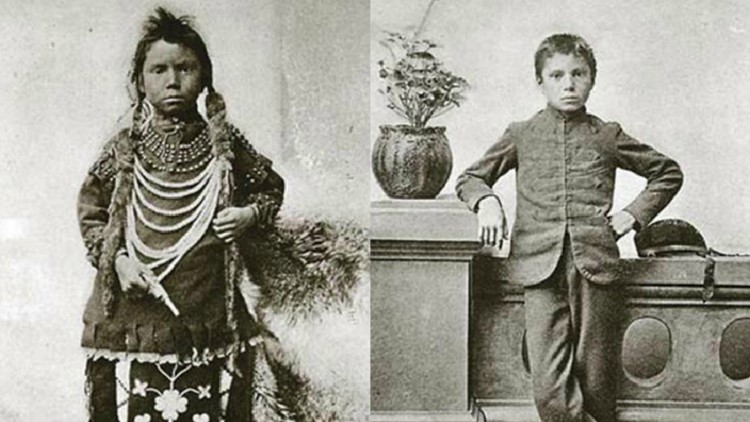

At boarding schools like the Carlisle School, students were stripped of their culture and taught the "white man's" way of doing things. Students often wore standardized uniforms instead of traditional garb, had their hair cut to reflect the current Western-style, were given new names, were forbidden to speak their native languages, and were made to adopt Christianity.

Disciplinary punishment in the form of beatings, starvation, and isolation was quite common at these schools, which has led to controversy as more is uncovered about what happened in these schools.

Many other schools followed the Carlisle School format, which became the standard across the country. Because they weren't allowed to practice their spirituality, speak their language, or live according to their culture, there was a loss of identity among Native Americans that still lingers in the 21st century.

Native American Boarding School Facts

- From 1869 to the 1960s, hundreds of thousands of Native American children were removed from their homes and families and enrolled in boarding schools

- In 1900, there were 20,000 children in native boarding schools

- Just 25 years later, that number climbed to 60,889

- By 1926, nearly 83% of Indian school-age children were attending boarding schools, some on and some off reservation

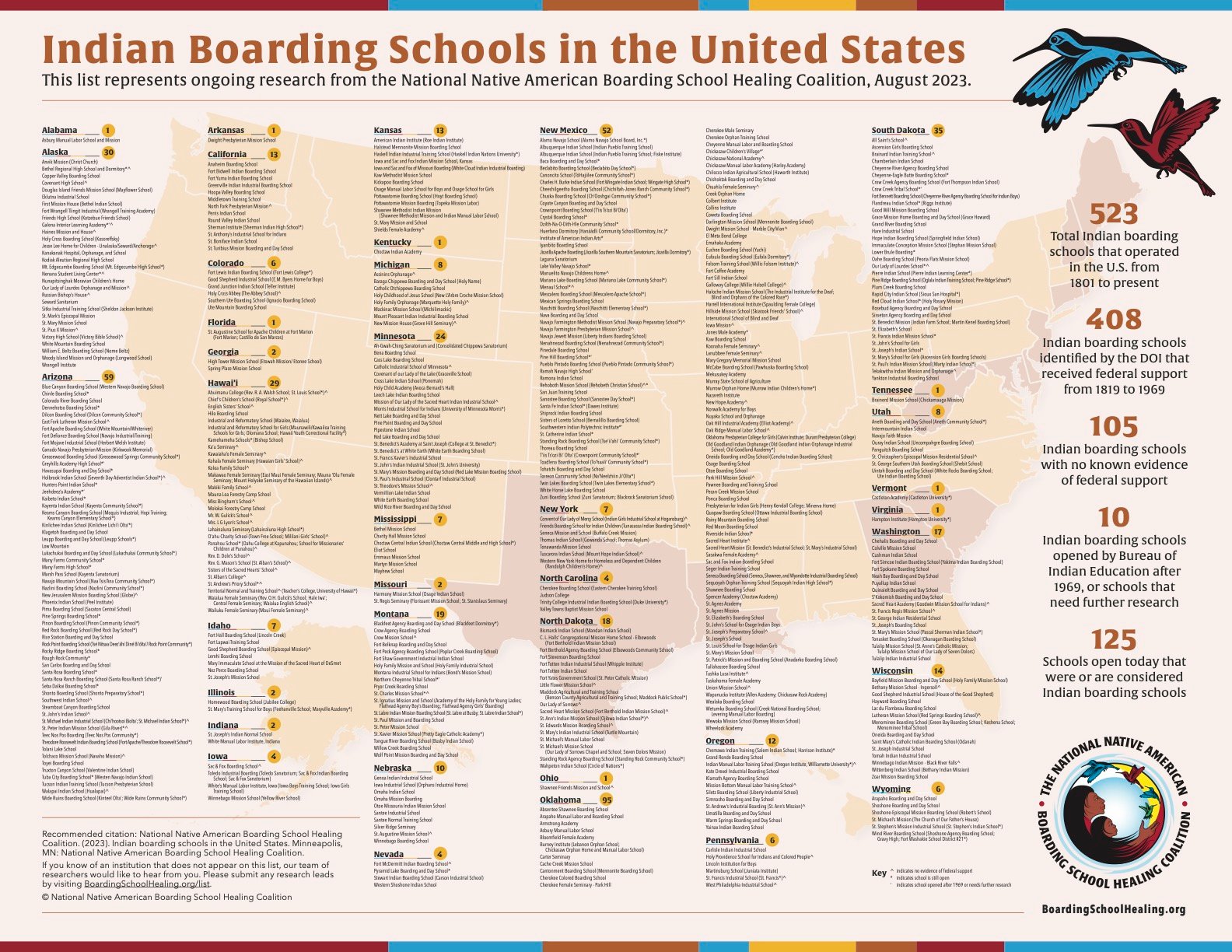

- There were 523 boarding schools operated in 29 states

- 125 schools remain in operation today

- Boarding schools were established by 14 different denominations, with Catholics, Presbyterians, and Quakers being the most common

- Today only 75 percent of Native students graduate high school—the lowest graduation rate among American students

When did Native American Boarding Schools End?

With the Meriam Report, the public began to become aware of the many inadequacies of boarding school life.

Published by the Institute for Government Research in 1928, the lengthy and oft-cited document detailed the results of a major study of Indian Tribes, exposing the widespread poverty on reservations, the poor conditions in Indian schools, and the failure of the U.S. government to improve the living conditions at Indian Schools.

The report was the stimulus for a great deal of reform and the closure of many of the government-run schools over the next several years.

As the public became more aware of the issues happening at the boarding schools, the federal government felt the pressure. It began a concerted effort to assimilate Native American students into public schools during the 1930s.

As the public became more aware of the issues happening at the boarding schools, the federal government felt the pressure. It began a concerted effort to assimilate Native American students into public schools during the 1930s.

Still, those schools that remained open provided an instrument for family preservation during the difficult era of the Great Depression.

While the boarding school system is responsible for creating ongoing societal problems among Native Americans today, there is not a strong historical memory of the notion that some Native American people themselves repeatedly sought out the schools for their children as a strategy of family preservation. Boarding school history, even during the Great Depression, demonstrates considerable Native American agency, and the ways in which families and students put limits on the (now declining) assimilative intentions of the institution.

Indeed, Native Americans were effective at limiting assimilation and reshaping those boarding schools that remained open.

In 2001, Congress passed the No Child Left Behind Act to raise the relatively low academic achievement of minority students, including Native Americans. Since the law's adoption, achievement has risen for every student group except Native Americans. However, there are still issues surrounding the education of Native American youth, including the lowest graduation rates of any demographic in the United States

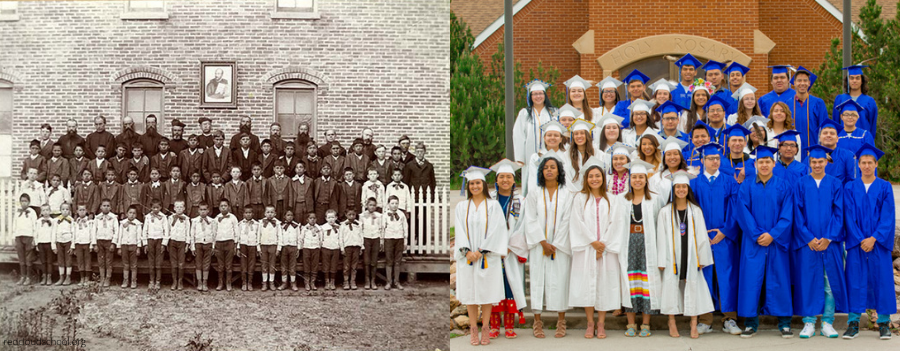

Fortunately, while some boarding schools are still open today, the practices around assimilation, punishment, and "civilizing" are no longer present, and many of these schools are actively involved in teaching language and culture.

Brenda Child, a citizen of the Red Lake band of Chippewa and the Northrop professor of American studies at the University of Minnesota, believes many Native Americans blame boarding schools for everything bad that ever happened to them under colonialism. She states, "The narrative doesn’t reflect the complexities and contradictions of the boarding school system, which was different for each generation."

Native American Schools Today

Despite the troubled past and the fact that there is still a lot of work to be done, some Native American schools are thriving today. These schools, along with the help of federal funding and nonprofit organizations, are trying to reverse the trends by providing a rich, holistic education in a safe environment.

Maȟpíya Lúta

Established by Jesuit Priests and Franciscan sisters in 1888, Maȟpíya Lúta, formally Red Cloud Indian School, was built in Pine Ridge, S.D.. Originally named The Holy Rosary School, it was renamed in 1969 both as a token of respect for the man whose work had made it possible to found the school and as part of a program of re-identification meant to demonstrate to the world that Red Cloud was not meant to be an organization of cultural imperialism, but rather the product of a lasting bond between separate cultures who wanted to enhance the best parts of both worlds to serve the people of the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation.

In response to the mass burials discovered in Canada and the United States, Red Cloud Indian School renamed its school and has become one of the leaders in the Truth and Healing movement for boarding schools.

St. Joseph's Indian School

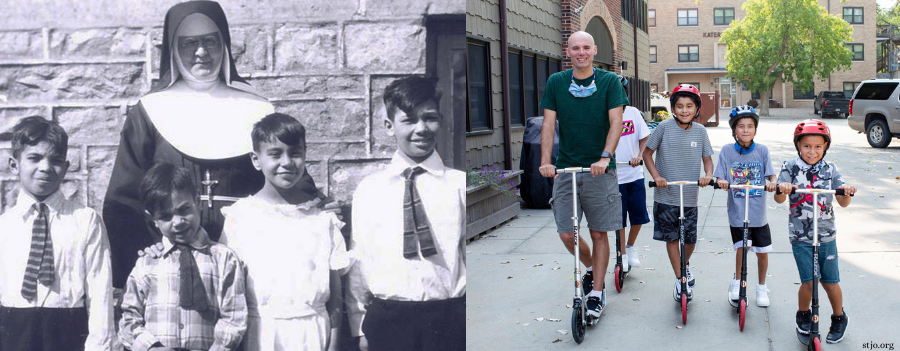

Located in Chamberlain, S.D., St. Joseph's provides quality education for more than 200 Native American children each year. The school was started in 1927 by Father Henry Hogebach SCJ, enrolling 53 students in its first year. Its fascinating history has helped it become one of the finest schools for Native American students in the United States today.

Its mission is to partner with Native American families and their children to educate them for life — mind, body, heart, and spirit. Culture, language and Native ceremonies are taught alongside the Catholic tradition. The wrap-around services that each student receives honor each student's specific needs as an individual.

Because families are such an integral part of a child’s education, health and growth, St. Joseph’s Indian School relies on members of a Parent Advisory Committee to provide insight and feedback on programs, services and challenges. The group consists of around a dozen individuals who are either parents, grandparents or guardians of students. Like Red Cloud, St. Joseph’s is part of the American Indian Catholic Schools Network and is involved it its Truth and Healing work.

These beliefs guide St. Joseph’s approach to students’ care and formation:

- Recognition of the dignity of all people as created in God’s image

- Belief in the student’s ability to progress and advance through strengths-based practice

- Strengths-based discipline or behavior management based on core values such as respect, caring, collaboration, resilience and possibility

- Mutual respect according to the staff/student role

- Courtesy and the Circle of Courage values of Belonging, Mastery, Independence and Generosity

- Flexibility based upon a child’s developmental level

- The transition from least-restrictive to most-restrictive consequence levels

- Personal relationships that enhance the opportunity for growth

- An environment that fosters the well-being of students and staff members because help is normative and harm of any sort is unacceptable

Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA)

The mission of the IAIA is, "To empower creativity and leadership in Native Arts and cultures through higher education, life-long learning, and outreach."

Established in Santa Fe, N.M. in 1962, the Institute has become an epicenter of art, culture, music, history, and research for the Native American community. With a top-tier museum and accredited higher education programs, the IAIA is one of a kind and an incredibly important part of the initiative to provide modern, quality education to Native Americans for generations to come.

.png?width=900&name=redcloudschool.org%20(1).png)

What is Orange Shirt Day?

Also called the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, September 30th is Orange Shirt Day. This day is set aside to recognize the trauma that residential schools inflicted on Native children and their self-esteem both while the children were in the schools and for decades afterward.

The movement was founded by Phyllis (Jack) Webstad, a survivor of residential schools. When Phyllis was six years old, she was put in a boarding school, where they took her brand new orange shirt and the rest of her belongings upon arrival, and never returned them. The disregard for Phyllis’s feelings, individuality, culture, pride, and autonomy became a visible representation to her of the calloused and stifling environment of the mission schools.

Orange Shirt Day now recognizes and raises awareness of the injustices and abuse that native children suffered in mission schools for years. It also commemorates the missing and murdered children forced to attend residential schools while honoring and giving a platform to the stories of residential school survivors. The day was officially recognized by the Canadian government in 2021, though it has been observed since 2013.

To participate in Orange Shirt Day, you can purchase a shirt here, or make your own. You can also organize a community event to raise awareness for the true history of residential schools and elevate Native voices.

We're on a mission to spread healing by telling the beautiful and tough stories that come from the Native American experience. Help us spread healing today and inspire hope. #StorytellingHeals

COMMENTS