Sep 30, 2024 | Hope McCloskey

Nine children started their final journey home from Carlisle, Pennsylvania. They made several stops along the way for prayer services. On the evening of July 16, 2021, they reached their destination surrounded by members of their nation at a town called Mission, located on the Rosebud Indian Reservation. It seemed like such a fuss for nine children, but they were finally going back home after a century of being gone.

Lucy Pretty Eagle

Rose Long Face

Ernest Knocks Off

Dennis Strikes First

Maude Little Girl

Friend Hollow Horn Bear

Warren Painter

Alvan

Dora Her Pipe

Those are the names of the children who made their way back after a century of being gone, lost and forgotten.

Repatriation is a big word and an unfortunate word to use in the context of children. Repatriation in this context means “the return of someone to their own country” or “the process of returning an asset, a symbolic item, or a person to their owner or their place of origin or citizenship, whether freely or violently.”

I haven’t heard the word much in the past, but lately, it has become a word that rolls off my tongue too frequently. There is always a big discussion about whether or not to repatriate in this situation. I always thought it should be up to the family. But what happens when the family is all gone?

On that same Friday evening, I made my way home too. I had been working at an internship with my old school and Native Hope. I decided to go home with my mom and enjoy the weekend. On the drive back, I had fallen asleep but woke up to my mother crying. Concerned, I asked her, “What’s wrong?” She just said that they left chairs, toys and balloons for the kids. Too tired to think things through, I went back to sleep.

After arriving home, my mom searched desperately for orange shirts, scarves, orange skirts, or anything orange. Again, I let it go without thinking too much about it. But soon after, she asked me if I was coming with her, and before I could answer, she threw my ribbon skirt at me and told me to hurry up.

Along the way, I finally asked her what we were doing. She explained that the kids were finally coming home, and that we have to be there for them. She got sad while explaining this next part. She informed me that these children had died and were buried at Carlisle Indian School. She said nine children of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe were coming back today to be buried tomorrow.

.png?width=716&name=Erin%20Bormett%20%20Argus%20Leader%20(1).png) I sat quietly, contemplating what she had just told me. Carlisle: It was a scary school to know about. It was what I perceived to be a nightmare, or the nightmare of Native American children back when they would take them from their parents and “reform” them: “Kill the Indian but Save the Man.”

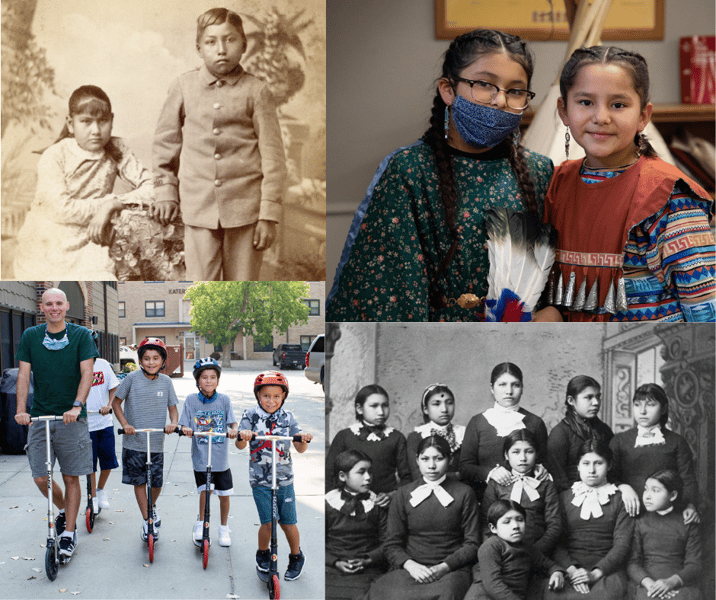

I sat quietly, contemplating what she had just told me. Carlisle: It was a scary school to know about. It was what I perceived to be a nightmare, or the nightmare of Native American children back when they would take them from their parents and “reform” them: “Kill the Indian but Save the Man.”

Horror stories came from that school, and I knew better than to ask my grandparents about what they thought of that time. Most of them went to boarding schools. None ever specified where they went, and none ever specified what had happened. That children had been buried at the school rather than returned to their parents didn’t come as a shock or a surprise. I just felt a sense of defeat, sadness and relief. Relief at knowing these kids were finally found. Sadness at knowing how lonely they were and how long they were gone. Defeat at knowing it took us this long to bring them home.

My mother, younger sister, brother and I drove a little outside my hometown, Mission, S.D., located on the Rosebud reservation. We parked alongside the road leading into town and waited. We weren’t the only ones waiting for the arrival of the children. Dozens of other cars and countless people waited at the town entrance to celebrate and mourn the arrival. Every single one of them was wearing long skirts, or something orange and holding posters. It was an overwhelming thing to see the community together for this occasion, but I also felt a sort of despair and melancholy in the people lined up there. I learned that the tribe and its people had decided to wear orange in memoriam for the children in this time. People should wear this to honor the kids coming home.

After an hour of waiting, they came. First, it started with a police and motorcade escort. Then came the vans and ambulances. But after that was the caravan of people who either were in the motorcade since the beginning of the trip from Carlisle or jumped in along the way. The whole thing lasted 10 minutes. It was heart-wrenching to know that those nine kids were somewhere in that long line of cars, making their way into town.

One woman we were standing next to said, “They’re finally home.” I couldn’t help but silently cry. Cry for the children who were taken —cry for all that they had suffered —and cry for the fact that they had never seen their families again.

Residential schools are among some of the most difficult things to talk about in the Native American experience. You have the stigma that Carlisle and Canada’s Marieval Indian Residential School brought to everyone’s imagination. But I attended a residential school for seven years of my life, St. Joseph’s Indian School located in Chamberlain, S.D., to be exact. They taught us the history of residential schools as well as their own history. It was never hidden or shunned.

We deserved to know things about those situations and the beginnings of our own school, and the school recognized that. Learning the truth about residential schools and what happened leading up to them, and after led me to think about the children returning home from a whole different perspective.

We deserved to know things about those situations and the beginnings of our own school, and the school recognized that. Learning the truth about residential schools and what happened leading up to them, and after led me to think about the children returning home from a whole different perspective.

I knew how things were back then, the abuse, the cutting of the hair, and the desperation to participate in the culture and language but being punished for that desire. It hurt to know that children had gone through all of this. At the same time, I had felt separated from it. I learned about it in school. My grandparents never discussed this part of their history, and no one else ever really did either.

So, to see the arrival of the nine children and to see them finally put to rest showed me that I was close to this and a part of it as well. I participated in a new system that acknowledged and taught Native American culture. In contrast, they participated in the older version, in which they were persecuted for having a culture at all.

I had a sense of guilt that I was able to experience something that they deserved. It’s not that I didn’t deserve it, but it’s that they hadn’t gotten even a taste of it before their deaths. Soon enough, I came to realize that my guilt was needless. The best any of us can do is respect them and honor their memory.

We're on a mission to spread healing by telling the beautiful and the tough stories that come from the Native American experience. Help us spread healing today and inspire hope. #StorytellingHeals

COMMENTS