Nov 24, 2016 | Native Hope with Trisha Burke

When I asked Nyal Brings Three White Horses [Brings] how he had become such a motivated man and mentor to others, he recounted a childhood memory involving his brother. He said, “We started the barn on fire. We were playing with the calves, and we started a fire. I don't know why, but we did,” Nyal confessed. “You could see the smoke for miles. People came over with water and helped put it out. We had to clean it up. We had to rebuild it again. It was made out of hay—every part,” he chuckled and sighed, “it was a pretty good size barn.”

At first I was puzzled when he came up with this story, but in the next breath, he explained that his parents motivated him.

Remembering his mother, Nyal lovingly said, “She was an industrious woman. She sold the cows. She canned the chokecherries. She took care of everything.” Nyal recounted, “My dad was always happy. He was a hard worker.”

His parents believed that “no wheel could turn without all of its spokes,” and this is how they raised their children. They encouraged them to gain an education, to work hard, and to hold on to their Lakota values.

Perhaps, it was Nyal’s upbringing on the small farm near the Little White River on the Rosebud Reservation in South Dakota (read part one of Nyal's story here) that gave him the simple tools he would need to survive in a complex world.

The inner flame

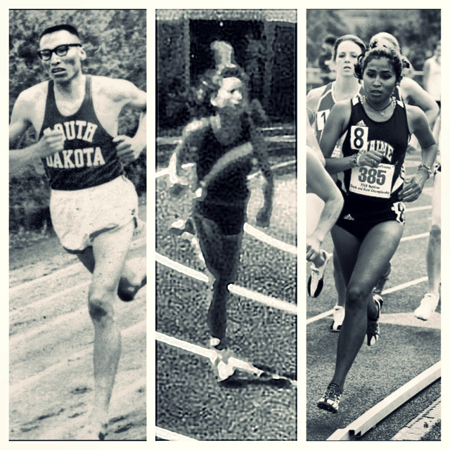

Nyal possessed an inner fire that drove him past the heartbreak of his missed opportunity to run for a spot on the 1960 Summer Olympic team (read part 2 of Nyal's story here) after suffering injuries in a car wreck that ended his chances of running in the trials.

“That fall, I did a little running, and some of the guys at the University of South Dakota (USD) wanted me to train them. So I did,” explained Nyal. “I ran with them...I trained them the way I trained. They became good and were conference champions.”

While at USD, Nyal attended graduate school for a master’s in education; however, when Nyal’s running mates graduated, he chose to leave USD before completing his degree. First and foremost in his life was being a member of a team, and when that camaraderie was gone, Nyal decided to go home to Rosebud.

He was offered a teaching and coaching job, but it only paid $5,000, so he opted to work for the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) overseeing ranchers and cattle grazing on reservation land. Nyal quickly realized that his desire to run still burned within, so in 1965, he left for California to seek out a running club.

The trail

Nyal worked making circuit boards for Fairchild rockets. In his spare time, he ran but mostly played a lot of basketball on nights and weekends with the Bay Area Sioux—eight guys from South Dakota.

Nyal found a new outlet in basketball and a group to which to belong. Playing ball became central to his life, and he was good at it. Nyal possessed a wingspan of over six feet! In fact, Nyal later became a member of the South Dakota Amateur Basketball Hall of Fame.

During this time, Nyal married Rita who had a son, John, and the couple had twins: David and Julie. With young children, Nyal and Rita decide to move back to South Dakota in 1969.

They moved to the Crow Creek Reservation where Nyal worked for both the Crow Creek Sioux Tribe and Lower Brule Sioux Tribe at the same time. “[For 5 years] I wrote all the grants for the funding of programs, some for Neighborhood Youth Corps,” shared Nyal. “I helped put a lot of kids to work,” he remembered with a nod of his head and a wide smile, “a lot of people to work.”

Nyal had a passion for helping others achieve their dreams and worked tirelessly to do so. His dream was to give others the opportunities he had been given.

The ups and downs

His marriage to Rita did not last, but Nyal found love with Darlene. They married shortly after he returned to South Dakota, and they had two children: Terra and Wade.

Eventually, Nyal made his way back to college. He attended Black Hills State in Spearfish, SD, where he earned his teaching certificate. Lower Brule schools hired Nyal to teach many subjects: language arts, driver’s education, history, and physical education.

Teaching at Lower Brule led him back to the track and court where he coached many young men and women to success, including his own children. He was living his dream!

In his daughter Terra, Nyal saw a bit of himself. At age four, Terra began running, and by age 10, she joined Nyal’s track team on the makeshift track behind his house. “She could keep up with them,” Nyal said with nostalgia.

In his daughter Terra, Nyal saw a bit of himself. At age four, Terra began running, and by age 10, she joined Nyal’s track team on the makeshift track behind his house. “She could keep up with them,” Nyal said with nostalgia.

Terra and Nyal spent hours upon hours together training. She performed any workout he wanted her to do. “I am very close to my dad. I wanted to please him,” Terra shared.

Nyal was meticulous about training, keeping notes about every aspect of his daughter’s workouts right down to the weather: wind speed and direction and the temperature. His dream was for Terra to make the 1988 Olympic team. This dream, however, would be halted in its tracks when Terra found out she was pregnant with her daughter, Jordan.

Terra recalled, “I tried to run a month after I had her, but I had her right before the trials, so that put a damper on things.” But she has no regrets because her daughter, Jordan, picked up the torch at age seven and started running with her Lala [Grandpa Nyal].

The torch is passed

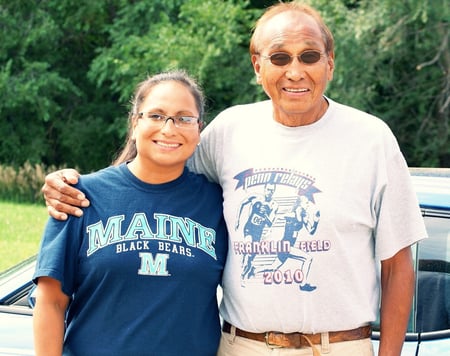

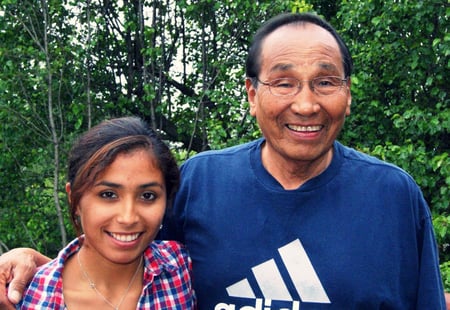

Jordan carries Nyal’s running legacy and holds Olympic dreams of her own. Nyal has passed the torch of determination and valiance to Jordan who reveres her grandfather’s dream of empowering young people with the tools to be successful in their own right.

In a letter to his grandchildren, Nyal wrote, “I don’t expect you to be an athlete like I was, you can do whatever you want, in order to keep busy and stay away from alcohol and drugs, because they only get you in trouble...talk to your mentors and elders if you feel like you need to talk to someone.”

Nyal believed in using the simple skill of communication to cope with complexities. He used stellar communication skills as a teacher, a Head Start coordinator, a grant writer, and a Tribal Health Director. His calm demeanor and tenacity enabled him to “get things done” on his reservation. This, too, has been passed on to his family and friends.

Nyal lost his nine-year battle with cancer and the side effects of treatment this past summer. He fought until the very end to pass on his knowledge of the Lakota culture and language and to help his people face the challenges of the reservation.

For many of us, Nyal’s encouraging words and cheerful optimism impacted us. He cared deeply for the Native youth and for their advancement in society. While he recognized that the barriers of race exist, he believed that there is always hope and opportunity to rise above and become the best we can be—balanced through good and bad.

For this and so much more, thank you, Nyal, for being an inspiration for so many, Native and non-Native. Much like the barn you and your brother set ablaze years ago, the sight of your flame will endure for generations to come.

The torch has been passed into safe hands.

Join the movement and invest in hope today.

COMMENTS