Nov 3, 2016 | Native Hope with Trisha Burke

At many points during his college career at the University of South Dakota (1956-1960), Nyal Brings Three White Horses [Brings] contemplated quitting school. “If you don’t finish school, what will you do—run the farm?” his mom asked. Although he loved the farm, he knew that running it was far from his aspiration of running in the Olympics.

Nyal also had a goal of being a teacher and a coach.

With the help of teammates, mentors, and coaches, Nyal pursued his dreams and continued his college career in spite of loneliness and discrimination.

One of his mentors was the famous artist Dr. Oscar Howe, the advisor for the USD Indian Club and the university’s Native American cultural center. “We went there to keep each other company and happy. There were seven of us,” explains Nyal with a chuckle. “We saved some Indian students from quitting like I did for like three hours.” See part 1 of Nyal's story here.

They would jump into Dr. Howe’s car and track down students who had “quit” college. “They were walking home, and we would take them back to school.” Nyal adds with a giggle, “One was almost all the way to Yankton (30 miles west of Vermillion).”

They would jump into Dr. Howe’s car and track down students who had “quit” college. “They were walking home, and we would take them back to school.” Nyal adds with a giggle, “One was almost all the way to Yankton (30 miles west of Vermillion).”

Nyal said that these students weren’t flunking; they were struggling to fit in. He recalls telling the kids, “Get back in here [the car]; school isn’t that hard. We’ll help you, and we’ll keep you company.”

As I listened to Nyal fondly recall this memory, I thought to myself, Here is the hero today’s generation needs.

Nyal’s upbeat and positive outlook in the face of adversity was remarkable. For many Native Americans, college proves to be too difficult. The cultural divide is deep, and finding a place in a world that harbors so many stereotypes is almost impossible.

Without mentors like Dr. Oscar Howe, young Native men and women would be lost. Nyal embraced his help along with the help of others and followed the pursuit of his goals.

On the track

Nyal’s talents as an athlete were the catalyst for his dreams. As a young boy at the BIA boarding school in Rosebud, South Dakota, he displayed a natural talent for running. He ran with the older kids just to pass the time.

“I ran because it made me feel good.” Nyal smiles and says, “I was able to beat runners, and that made me feel good, too.” The truth is that Nyal enjoyed the feeling of victory, but he lived his life with the philosophy that we all must “accept winning and losing” and that we should “be confident, not cocky—taking pride in our abilities.”

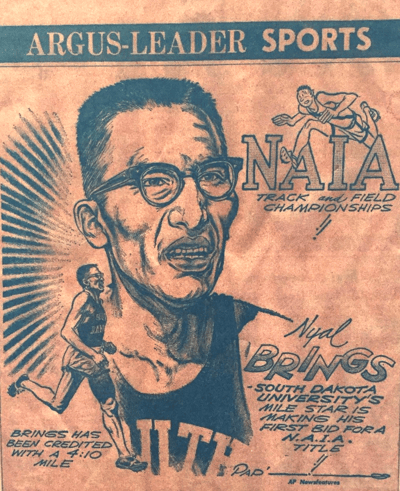

Nyal ran for the university on a full scholarship and was considered one of the premier distance runners in the Midwest and one of the best ever in the history of South Dakota track and field. During his career, he racked up victory after victory in the middle distances.

Not only was Nyal known for his speed but also for his sportsmanship. His Lakota values led his actions, always showing humility and nobility. He believed in showing respect in all his relationships: teammate to teammate, competitor to competitor.

When I asked Nyal about his favorite memory from his running career, there was no hesitation: “Beating my friend Billy Mills.” Billy Mills, who went on to become the 1964 Olympic gold medalist in the 10,000 meter race, was a Native from Pine Ridge, South Dakota, who ran against Nyal at the Drake Relays in Des Moines, Iowa, in 1959 and 1960.

Listening to Nyal recount the two victories in the mile over Billy is joyous. Nyal relived every moment. He was there, pounding the track and striving for the finish line.

Nyal finished his senior year, 1960, winning race after race; in fact, he was undefeated in the 880-yard races gathering twelve consecutive wins. He was destined for the 1960 Olympics!

On the road

In May of 1960, Nyal graduated from USD. He was the second Native American from his town and the first in his family to earn a college degree. Now, he could focus on qualifying for the Olympics in two events: the 880 and 1500.

The trials would take place in California at Stanford University in July. He trained at home and USD. While in White River, he ran a six to seven mile trail through the pastures of his family farm in the heat of the day, often multiple times.

But Nyal admits that his training was haphazard at home, so he decided to pack up and go back to Vermillion where he had a set routine and route. Unfortunately, he would not make it back to USD.

On his way back to Vermillion, he had a car wreck. “I was speeding. I was going 60 mph on a gravel road, and another car was coming, so I moved over,” Nyal solemnly recalls. “I rolled the car four or five times. When I awoke, the car was on fire, and I was still inside it. I crawled out by myself. I hurt my head, ankle, thigh, and back. The postman spotted me and helped me put out the fire…he took me to the clinic in White River.”

Nyal knew his bid for the Olympics was over. “I was angry; it was caused by me,” he says.

However, like everything in his life, he took this defeat with grace and used his talents to help those who had enabled him to reach his potential. In the fall, his friends asked him to come back to Vermillion to help them train. Nyal gladly returned to USD to help his teammates and to pursue a master’s degree in education.

Once again, he displayed his selflessness as he willingly helped others achieve their goals. In the years following his college career, Nyal’s pursuit for happiness and fulfillment would take him many different directions, leading him all the way to California and back to South Dakota.

Read part 3 of Nyal's story "Passing the Torch."

Join Native Hope as we seek to inspire a generation with hope.

COMMENTS