Mar 20, 2017 | Native Hope

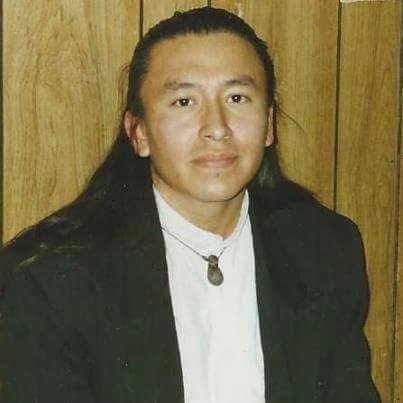

“I’m on a mission. I want to bring hope. I want to challenge how people perceive their world so we can heal and diversity can flourish,” explains Reuben Fast Horse, a member of the Hunkpapha Lakota from the Standing Rock Reservation in South Dakota—Chief Sitting Bull’s Tribe.

Becoming a true Lakota

“It wasn’t until we went to school with farmers and ranchers that I realized I was Indian [at age 8],” explains Reuben.

In fact, identity eluded Reuben for many years. He spent his childhood on the Standing Rock Reservation in northwestern South Dakota during the 1970s. There, he attended an elementary school where the ratio of non-Natives to Natives was nine to one.

That was his world—a world where he only heard his Native language, Lakota, at night as he lay on the floor listening to his parents “cut loose in their tongue.”

“I slept on the floor. The adults were in the kitchen: my mom, dad, grandmas, grandpas, aunties, and uncles,” Reuben reflects. “We had no TV, so I would listen. This became my true impression of the language. I associated the language with the jovial—joking and teasing—with laughter!”

The language remained a tether, tying all of them to their Lakota roots.

Reuben fell asleep to their stories. The beauty of the laughter, mingled with his Lakota language, was a feast for his ears. It gave him a sense of identity and comfort, as well as the first recollection of his language.

The trek

While Reuben is a member of the Hunkpapha Lakota, he admits that finding his identity has been an ongoing process; however, the Lakota language has always been at the root of his trek.

After elementary school, his family moved to Pine Ridge when Reuben’s father took a job at the Loneman School. “When we moved to Pine Ridge, we went to an opposite ratio of non-Natives to Natives: one to nine,” Reuben expounds. “A kid with braids walked by us, and I said, ‘That’s a real Indian!’”

He continues, “At the Loneman School, everyone spoke in Lakota, and my dad loved it, and they loved him. He introduced us [Reuben’s family] to the Oglala people.”

Later, Reuben attended Red Cloud High School. His father was a businessman and wore a suit and tie every day, and so did Reuben. “I was contrary," he explains. "I wore a suit and listened to heavy metal music. I didn’t care about being Native; I didn’t dance.”

Not dancing meant that Reuben didn’t participate in powwows; he was not “traditional." Reuben was a “contrarian”—one who rejected the popular opinion. Fitting in was not Reuben’s goal; he was driven to be more, holding on to aspirations of attending college to be like his dad.

Because of his personal goals and his style, Reuben experienced the typical bullying from the majority.

In conflict or in struggle, he recalls that his dad always said, “Help them. If others are making fun of you, help them!”

Reuben laughs, “Eventually, I knew how to take care of myself with my verbal skills—jokes about myself. Used my wit.”

His witticism led him to “making fun of the language [Lakota].” Reuben relates, “My friends and I would joke around. We knew we were Lakota and that there were no curse words in Lakota."

At this point in his life, Reuben didn’t understand the cost of making light of one’s culture—he was young and unknowing of the great role his heritage would play in his life. Read part two of Reuben's story here.

Native Hope and our partners seek to promote the revitalization of Lakota, Dakota, and Nakota. We are committed to exposing young Native Americans to their languages by supporting the efforts of speakers like Reuben who are dedicated to ensuring that the languages live.

COMMENTS